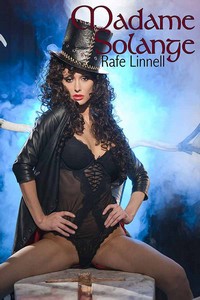

EXTRACT FOR

Madame Solange

(Rafe Linnell)

|

Man's Only Escape From her is the Grave... Or is it? Bernard Cromwell Bernard Cromwell, my friend of indeterminate class and film-star good-looks, departed the shores of England near a decade ago for destinations he, out of necessity, did not share with me. But it is only now, armed with his imminent re-entry into my life along with the full-story - or as full as third-person experience allows given his absence; that conscience sees fit to free me from the promise of secrecy I made him with sad but genuine intent at that time. An intent as sacred to me then as the strength of our friendship, despite that absence, remains real still. Of course, I am no paragon of moral rectitude and no slave, fettered and bound, to my word. If, that is, I believe it was coerced from me under false circumstances in the first place. But where possible, and notwithstanding the fickle weaknesses of mind and flesh, I do feel a duty to keep myself to that word under certain correct circumstances. Circumstances such as those I am about to relate along with, I must confess, a strong impulse - need even - to break my near decade of silence and confide my friend's curious history to the confessional that is ink and paper. An impulse that does not find itself diluted by the telegram - the same brief and elliptical missive that was only the second communication of its kind he had sent me in his absence - I received some seven weeks ago. A telegram telling me that he is on route to Blighty and to be so good as to have the affairs he entrusted to me upon leaving in order before his return. Affairs that involve having the cottage I had rented out for him during his absence free and ready for occupation when he arrives in what, now, will be no more than a few days or so. Along with which expectation, I feel obliged to add, comes a sudden and troubling concern that all is not right in my own otherwise settled world and that troubles made all the more worrying for being unfathomable are winging their way towards me - this, even as I relate to you those under which a person other than myself labours. The above despite the fact that this should be a time of some celebration for me, given that my once steadfast vow of bachelorhood is about to be stripped from my once steely grasp - much to Cromwell's surprise when he arrives, I have no doubt - by the sweet but indomitable young lady who has made it her mission to save me from what, in her book at least, is a waste of monumental proportions. Miss Estelle Castlereagh. A pretty young woman almost half my years who not only had to overcome my own doubts and misgivings but those of her parents too. The same Castlereagh's who own a fair proportion of the land upon which our village stands as well as great swathes of the Weald in Kent and the Estuary towns of Essex. The daughter's feelings for their older neighbour not made any easier to bear for both mother and father having known their daughter's new love-interest at university. But there it is. My former fellow students have bitten hard upon the bullet and so must I. Though I fancy my sacrifice when compared to theirs to be of the far less onerous variety. And so it is that I begin a tale of horror and degradation I would once have believed solely the province of the more fanciful writers of yore I so enjoyed in my formative years. The writers of those same stories I can no longer bear to countenance. Knowing as I do now the reality often to be found behind their fictional offerings. Poe and Le Fanu but two of the above masters who once excited my youthful imagination; as well as another whose name will prove familiar to many of you for whom horror was not the prime idee fixe it was with the others, but whose short-stories on the subject - and one in-particular - exert a huge influence on the segment of biography I am about to relate. The biography in question being that of my aforementioned friend and the abomination of a woman who sent his life into a freefall of unwilling service and sexual humiliation at her hands. As well as at her well-shod feet and the equally well-tended lower extremities of the outrages masquerading in female form she described as her... "intimates". Any description of Cromwell's fate, of course, will not be for the fainthearted or those of a more timorous sexual persuasion - even in these more enlightened times; but I will not hold back from a re-telling I hope will be as near to the truth as I can make it and still remain publishable to future generations. This while being accepted as the fact and not fiction that it is. The name I chose to call myself for the purposes of anonymity, much as I chose "Bernard Cromwell" and any others you may come across, is Daniel Frome-Hardy. And you have been warned... Daniel Frome-Hardy Cliffe Cottage Chrome Chart Sussex October 1935 Chrome Chart

The village of Chrome Chart in East Sussex is as affluent as any village in this favoured Home-County and, surprisingly, has an eclectic - for this timeless corner of the green and pleasant anyway - mix of society. Here there are farmers, old-fashioned but worldly and affluent just the same, who employ farm-hands for whom a simple train-journey to London would seem no less exotic than taking berth on a Cunard-Line steamer bound for far off Bali. Country-Squires, resolute in the old class-structures and as unbending as cast-iron in the face of a light but no less unwanted wind, intermingle in the shops and hostelries with retired London Haberdashers and upward looking merchants. Not forgetting the salesmen and other Johnny-Come-Lately's who would not know an aspirate from an Aspirin. And would be no better placed when it came to enunciating one correctly if they did. Add to the above mix the usual legal and medical professionals and some ex-forces personnel from Land, Sea, and Air, while throwing in a few inevitable literary scribblers; along with the wives, daughters and mothers who do so much to keep the brute male in civilised social order - sometimes successfully; and you are in possession of a reasonable demographic of the village that is my home still. Nobody in that village, however, including your writer, seemed to know to which class Bernard Cromwell of the film-star looks should be assigned. An uncertainty in them explained by the fact he moved as easily in the drawing-rooms of the squires as he did when in the local pub amongst the farm-hands partaking of the hop. A diversion they took that they might forget for a while the unpromising manual futures awaiting them in the fields, barns, and milking-sheds toiling for the farmers who employed them. Cromwell's easy acceptance into these differing pockets of village life I always fancied was down to his image as an exceedingly handsome man and eccentric bachelor who seemed utterly devoid of side. Not forgetting the air of mystery that cloaked his past as well as his sudden and still unexplained entry into village life. But whatever the explanation, he was soon accepted into each of our village societies which, in most cases, remained closed off one from each other. Or at least they did to me. Your writer, you see, not possessing either then or now a smidgen of Cromwell's social gift. Though my exclusions were mostly from the more prosaic cliques - if I might use the description without my readers thinking of me as the inveterate snob I possess enough in the way of self-awareness to recognise myself as being. Part of the explanation for this acceptance attributable to my new friend's above-mentioned gift for inclusiveness with those from all walks of life, though I'm sure his undeniable good looks - and an almost uncanny resemblance to an actor who is by now well-known in Hollywood - contributed hugely also. Not forgetting a rakish charm that made women desire him and men seek his friendship. As well as the fact that, along with me, he was wealthy and - again in common with his friend and chronicler - a confirmed if, as inferred from the description, somewhat lackadaisical sybarite. Just the same, personal similarities aside and village life in England being what it is, I had known Bernard Cromwell for some years before we became at all friendly. Perhaps because, at least at first, he fascinated and repelled as much as he intrigued and puzzled me. A distance on my part explained somewhat by a certain base reason in regard of his attraction for the fair-sex. A base reason I confess serves me no credit when I think hard upon it - even if I was no woman's idea of a Victorian carnival attraction and should not have been envious of the physique and facial bounty nature had seen fit to award him. No matter. I was not so vain that I allowed my envy to spill over into outright jealousy. Not often, at any rate; though it did come as a surprise when we became the very best of friends. Describing him, I have to say, and except in the general terms I've already set to paper, is not easy. Mainly because there always seemed to me to be so many forms of him he showed to the world. As likeable and charming as he could be, he remains, something of an enigma to me still. Protean. Often, it would seem while in conversation with him that he was no more than a physically well put together simpleton; only to learn, the longer the conversation lasted, that the real fool was the one accepting of such a suspicion in his regard. He could seem quite fanciful and something of a romancer at times, but one's thoughts had scarcely finished describing him as a liar and a fantasist when something in his speech refuted the thought and seemed to insist that, if one was once able to get behind the surface word he seemed to use in order to win a favourable impression from his listeners, one would find a man and a friend it was possible to trust with one's most valued secrets or, even, one's life. It was, as our growing friendship would eventually prove, the more reliable of my impression's on his behalf. And changed what had befallen him and what was about to again not one whit. Suffice it to say that, during the tenuous and fledgling beginnings of our association I was many times left with the uncomfortable suspicion that, instead of treating me as a peer and an equal, he had somehow been deconstructing me with a view to discerning my own personal - and many - weaknesses. Analysing me in such a way that he might use my failings for his own ends. Though as far as other's regard of him went, he seemed to possess as much concern for how people viewed what they saw of him as the tea-cup for the departing tray upon which it had just been delivered. In this latter regard, Cromwell was utterly impervious. |